An ankle sprain is one of the most common soft tissue injuries experienced. It is estimated that up to 100 000 ankle sprains occur each year in Canada. Spraining an ankle can happen to virtually anybody, whether during vigorous physical activity and sports, or from something as simple as losing your balance or stepping onto an uneven surface during everyday tasks.

In most high school and college level sports ankle sprains are the number one or two most frequently reported injury for both men and women with basketball, soccer and volleyball players being the most at risk. Unfortunately, there are very few definitive risk factors to watch out for that predict ankle sprains. Some factors such as flexibility, strength and excessive pronation can provide some indication to future sprains, but the results of studies researching these are still unclear. One single factor that has consistently shown to be a risk factor for future ankle sprains is past ankle sprains. This is a major reason why proper treatment is key for full recovery of an ankle sprain and to decrease the chances of sustaining a similar injury in the future.

Typically, a person sprains their ankle through excessive inversion, or rolling over onto the outside of their foot. This can occur during any walking, running or jumping activity and happens immediately after the foot makes contact with the ground, as this is when the joint is in its least stable position. Sometimes a sprain can occur when stepping or landing on an uneven surface, for example, another athlete’s foot during a game. This excessive inversion motion stretches the ligaments of the ankle past the point of which they are capable and results in a partial or complete tear. The most common signs and symptoms that indicate a sprained ankle are: pain at the top or outside of the foot when weight bearing or during certain movements; swelling; bruising; reduced range of motion; and for more severe sprain’s, sometimes a distinct popping sound at the moment of injury.

Typically, a person sprains their ankle through excessive inversion, or rolling over onto the outside of their foot. This can occur during any walking, running or jumping activity and happens immediately after the foot makes contact with the ground, as this is when the joint is in its least stable position. Sometimes a sprain can occur when stepping or landing on an uneven surface, for example, another athlete’s foot during a game. This excessive inversion motion stretches the ligaments of the ankle past the point of which they are capable and results in a partial or complete tear. The most common signs and symptoms that indicate a sprained ankle are: pain at the top or outside of the foot when weight bearing or during certain movements; swelling; bruising; reduced range of motion; and for more severe sprain’s, sometimes a distinct popping sound at the moment of injury.

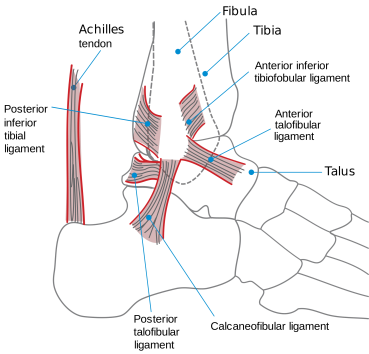

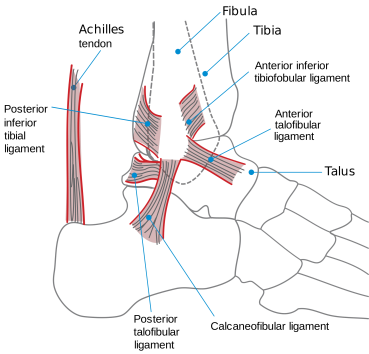

The most commonly injured ligament during an ankle sprain is the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL), which connects the fibula (one of the lower leg bones) to the top of the foot. The second most commonly injured ligament is the calcaneal fibular ligament (CFL). This ligament connects the same lower leg bone to the calcaneus, or heel bone. Occasionally, a ligament called the anterior inferior tibiofibular ligament (AITFL) is affected during a high ankle sprain. In this injury, the pain is located more in the front of the lower leg than in the foot. It is important to not overlook this symptom because high ankle sprains often have a much longer recovery period.

The most commonly injured ligament during an ankle sprain is the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL), which connects the fibula (one of the lower leg bones) to the top of the foot. The second most commonly injured ligament is the calcaneal fibular ligament (CFL). This ligament connects the same lower leg bone to the calcaneus, or heel bone. Occasionally, a ligament called the anterior inferior tibiofibular ligament (AITFL) is affected during a high ankle sprain. In this injury, the pain is located more in the front of the lower leg than in the foot. It is important to not overlook this symptom because high ankle sprains often have a much longer recovery period.

Ankle sprains can be graded into 3 categories:

Grade 1:

- Very slight tear of ligament fibres, no significant structural damage

- Swelling, pain and instability is minimal

- Treatment: Weight bearing as tolerated, range of motion and stretching exercises with quick progression into strengtheningexercises

Grade 2:

- Partial tear of ligament

- Moderate swelling, pain and instability, decrease in range of motion

- Treatment: immobilization if necessary, only pain free range of motion exercises, slower progression of stretching and strengthening exercises

Grade 3:

- Complete rupture of ligament

- Significant swelling, pain and instability, unable to weight bear

- Treatment: Short-term immobilization with cast/crutches, similar progression as grade 2 but over longer period of time, surgical reconstruction occasionally recommended

How Physiotherapy Can Help:

Because ankle sprains are so common, there is a misconception they do not require much treatment and you should just ‘walk it off’. Many people assume that once the pain of an ankle injury subsides, they have fully recovered. But, without seeking treatment from a physiotherapist, regardless of the severity of the injury, lasting symptoms can be a problem with activity and increases the chance of re-injuring the weakened structures. People who do not seek treatment can experience long term issues such as pain, instability and stiffness, which can remain problems for months or even years after the injury occurred.One research study discovered that as many as 75% of people who have sustained an ankle injury report residual symptoms more than 1 year after the injury occurred.

Stiffness is the most common complaint in the later healing phases of an ankle injury, which can be present for months,and is often ignored. This stiffness is not likely to disappear on its own without proper treatment and joint mobilizations from a physiotherapist. Incomplete recovery of an ankle sprain leading to instability or pain in the ankle joint may cause compensation by other joints or muscles in the lower body. The compensation often changes normal walking and running patterns, causing them to become unnatural and inefficient,placing unexpected stress on other structures in the legs and hips. This stress creates an ideal environment for injury, so it is not uncommon to see lower back, hip or knee pain in people with a history of an unresolved ankle injury.

Seeing a physiotherapist after an ankle sprain can help you return to your pre-injury activity levels as quickly as 3-8 weeks, depending on the severity of the sprain. The primary treatment goals after an ankle sprain are to protect the structures of the foot from further damage and to reduce pain and swelling. This is accomplished through protected weight bearing (using crutches or air cast if necessary for more severe sprains), ice, compression and elevation, followed by pain free range of motion exercises. Research completed on the use of ice has shown it to be most effective when applied in the first 36 hours after the injury. Apply for 10 minutes on, 10 minutes off and repeat. Once the healing process has begun, your physiotherapist will assist you in fully restoring your range of motion, and begin to strengthen and promote stability in your ankle joint. Increasing stability in your ankle is a very important part of recovery, as it will help prevent chronic pain and greatly reduce the chance of another ankle injury down the road. In the final phase of treatment, the goal is to return you to your original strength and power levels, which is achieved through more difficult balance and functional activity exercises. This phase of treatment is very important because early return to activity without completing a comprehensive strengthening program can result in re-injury of the ankle.

Prevention of Injury:

Using prevention strategies can help reduce the chance of an ankle sprain from even occurring in the first place. Ensuring that you begin each sport or activity with a proper warm up is very beneficial for preventing any type of injury. As outlined in a previous blog post, a dynamic warmup will increase circulation, warm your muscles and prepare your joints for exercise.Warming up for a minimum of 5-10 minutes will allow your joints to move through a greater range of motion with ease, which will reduce the chance of ligament or muscle tears.Strengthening the muscles within the lower leg and foot will also help in preventing injury. There is a group of muscles along the outer side of the lower leg and foot called the peroneals. Research has indicated that strong peroneals reduce the amount of inversion, which is the most common mechanism of injury for ankle sprains. Strengthening the peroneals can be accomplished by performing calf raises on a flat surface or from a step, or walking on the toes.

Many people complain of feeling unstable through the ankle joint, and practicing balance exercises can be a great way to combat this problem. One simple way to fit this into your everyday life is to try to stand on one foot while doing an activity such as brushing your teeth or washing the dishes. Once this exercise becomes easy, more difficult modifications can be made by closing your eyes, standing on a pillow or hopping on one foot. While beneficial for everybody, balance exercises are especially important for those who are trying to prevent a second ankle injury.Using a brace or taping your ankle can also help reduce the risk of a second ankle sprain, but this should only be a short term fix as you continue to strengthen and stabilize your ankle structures.Ensuring proper footwear during any physical activity is another key way to prevent ankle injuries. Your shoes should fit well through the toe box and have a good amount of both cushioning and stability at the heel.

Visiting a physiotherapist to address your ankle injuries or instability will help prevent any long term problems. Getting proper treatment will greatly reduce the chance of further ankle injuries or any other injury that may result from compensation due to pain or instability of the ankle joint.

Medial tibial stress syndrome, commonly called “shin splints”, is a term used to describe pain and tenderness felt on the inside, lower border of the shin bone. Shin splints are commonly experienced by athletes who take part in activities involving repetitive running and jumping, particularly after a sudden increase in activity level (either duration, distance or intensity). The repetitive stress placed on the bones, muscles and joints of the lower leg during these high impact activities may result in irritation and inflammation of the shin bone (tibia).

Medial tibial stress syndrome, commonly called “shin splints”, is a term used to describe pain and tenderness felt on the inside, lower border of the shin bone. Shin splints are commonly experienced by athletes who take part in activities involving repetitive running and jumping, particularly after a sudden increase in activity level (either duration, distance or intensity). The repetitive stress placed on the bones, muscles and joints of the lower leg during these high impact activities may result in irritation and inflammation of the shin bone (tibia). There are a number of factors that may predispose an athlete to develop shin splints including: flat feet, rigid arches, muscle weakness, and/or muscle tightness. Other contributing factors may include running downhill, running on hard surfaces, running in worn-out footwear, or playing sports with frequent stops and starts (e.g. basketball, squash, tennis). While the pain presentation is often similar across individuals, there are a variety of bio-mechanical abnormalities in the pelvis, hips, knees, and ankles that can also lead to the development of shin splints.

There are a number of factors that may predispose an athlete to develop shin splints including: flat feet, rigid arches, muscle weakness, and/or muscle tightness. Other contributing factors may include running downhill, running on hard surfaces, running in worn-out footwear, or playing sports with frequent stops and starts (e.g. basketball, squash, tennis). While the pain presentation is often similar across individuals, there are a variety of bio-mechanical abnormalities in the pelvis, hips, knees, and ankles that can also lead to the development of shin splints.

Typically, a person sprains their ankle through excessive inversion, or rolling over onto the outside of their foot. This can occur during any walking, running or jumping activity and happens immediately after the foot makes contact with the ground, as this is when the joint is in its least stable position. Sometimes a sprain can occur when stepping or landing on an uneven surface, for example, another athlete’s foot during a game. This excessive inversion motion stretches the ligaments of the ankle past the point of which they are capable and results in a partial or complete tear. The most common signs and symptoms that indicate a sprained ankle are: pain at the top or outside of the foot when weight bearing or during certain movements; swelling; bruising; reduced range of motion; and for more severe sprain’s, sometimes a distinct popping sound at the moment of injury.

Typically, a person sprains their ankle through excessive inversion, or rolling over onto the outside of their foot. This can occur during any walking, running or jumping activity and happens immediately after the foot makes contact with the ground, as this is when the joint is in its least stable position. Sometimes a sprain can occur when stepping or landing on an uneven surface, for example, another athlete’s foot during a game. This excessive inversion motion stretches the ligaments of the ankle past the point of which they are capable and results in a partial or complete tear. The most common signs and symptoms that indicate a sprained ankle are: pain at the top or outside of the foot when weight bearing or during certain movements; swelling; bruising; reduced range of motion; and for more severe sprain’s, sometimes a distinct popping sound at the moment of injury. The most commonly injured ligament during an ankle sprain is the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL), which connects the fibula (one of the lower leg bones) to the top of the foot. The second most commonly injured ligament is the calcaneal fibular ligament (CFL). This ligament connects the same lower leg bone to the calcaneus, or heel bone. Occasionally, a ligament called the anterior inferior tibiofibular ligament (AITFL) is affected during a high ankle sprain. In this injury, the pain is located more in the front of the lower leg than in the foot. It is important to not overlook this symptom because high ankle sprains often have a much longer recovery period.

The most commonly injured ligament during an ankle sprain is the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL), which connects the fibula (one of the lower leg bones) to the top of the foot. The second most commonly injured ligament is the calcaneal fibular ligament (CFL). This ligament connects the same lower leg bone to the calcaneus, or heel bone. Occasionally, a ligament called the anterior inferior tibiofibular ligament (AITFL) is affected during a high ankle sprain. In this injury, the pain is located more in the front of the lower leg than in the foot. It is important to not overlook this symptom because high ankle sprains often have a much longer recovery period.

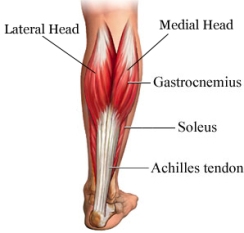

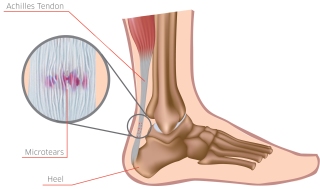

The Achilles tendon is the largest tendon in the body. This tendon originates at the junction of the two calf muscles: gastrocnemius and soleus, and then inserts into the heel. The gastrocnemius-soleus musculotendinous unit is responsible for plantarflexion of the ankle and flexion of the leg at the knee. We use these powerful calf muscles for explosive activities like running and jumping, and the Achilles tendon transmits these forces down to the ankle joint. These constant stresses placed on the Achilles tendon increase the chance of injury. Additionally, due to the poor blood flow of the tendon, overuse or overloading in combination with inadequate healing time can lead to injury.

The Achilles tendon is the largest tendon in the body. This tendon originates at the junction of the two calf muscles: gastrocnemius and soleus, and then inserts into the heel. The gastrocnemius-soleus musculotendinous unit is responsible for plantarflexion of the ankle and flexion of the leg at the knee. We use these powerful calf muscles for explosive activities like running and jumping, and the Achilles tendon transmits these forces down to the ankle joint. These constant stresses placed on the Achilles tendon increase the chance of injury. Additionally, due to the poor blood flow of the tendon, overuse or overloading in combination with inadequate healing time can lead to injury.

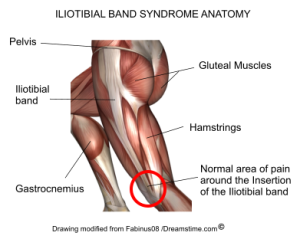

The Iliotibial band (ITB) is a thick band of fascia that runs down the outside of the thigh and on the outer aspect of the knee as it continues down to attach on the tibia. Both the tensor fasciae latae and gluteus maximus muscles insert on the ITB. The attachment of the ITB below the knee joint allows the tensor fasciae latae to abduct, medially rotate and flex the thigh, and gluteus maximus to externally rotate the thigh. Both muscles also function to stabilize the knee during extension in walking and running.

The Iliotibial band (ITB) is a thick band of fascia that runs down the outside of the thigh and on the outer aspect of the knee as it continues down to attach on the tibia. Both the tensor fasciae latae and gluteus maximus muscles insert on the ITB. The attachment of the ITB below the knee joint allows the tensor fasciae latae to abduct, medially rotate and flex the thigh, and gluteus maximus to externally rotate the thigh. Both muscles also function to stabilize the knee during extension in walking and running.